Formatting properties

XSL Formatting Objects (XSL-FO) are the second half of the Extensible Stylesheet Language (XSL). XSL-FO is an XML application that describes how pages will look when presented to a reader. A style sheet uses the XSL transformation language to transform an XML document in a semantic vocabulary into a new XML document that uses the XSL-FO presentational vocabulary. While one can hope that Web browsers will one day know how to directly display data marked up with XSL formatting objects, for now an additional step is necessary in which the output document is further transformed into some other format, such as Adobe’s PDF.

XSL-FO provides a more sophisticated visual layout model than HTML+CSS. Formatting supported by XSL-FO, but not supported by HTML+CSS, includes right-to-left and top-to-bottom text, footnotes, margin notes, page numbers in cross-references, and more. In particular, while CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) is primarily intended for use on the Web, XSL-FO is designed for broader use. You should, for instance, be able to write an XSL style sheet that uses formatting objects to lay out an entire printed book. A different style sheet should be able to transform the same XML document into a Web site.

A Word of Caution about XSL Formatting Objects

This chapter is based on the October 15, 2001 Recommendation of the XSL specification. However, most software does not implement all of the the final recommendation for XSL. In fact, so far there are only a few standalone programs that convert XSL-FO documents into PDF files. There are no Web browsers that can display a document written with XSL formatting objects. Eventually, of course, this should be straightened out as more vendors implement XSL formatting objects.

There

are exactly 56 XSL formatting object elements. These are placed in

the http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format namespace. At

least 99 percent of the time, the chosen prefix is fo.

In this chapter, I use the fo prefix to indicate

this namespace without further comment.

Of the 56 elements, most signify various kinds of rectangular areas. Most of the rest are containers for rectangular areas and spaces. In alphabetical order, these formatting objects are:

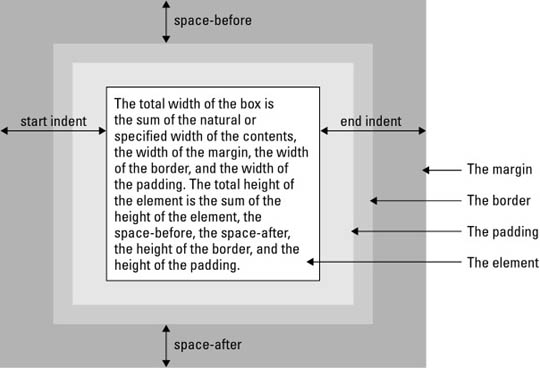

fo:basic-linkfo:bidi-overridefo:blockfo:block-containerfo:characterfo:color-profilefo:conditional-page-master-referencefo:declarationsfo:external-graphicfo:floatfo:flowfo:footnotefo:footnote-bodyfo:initial-property-setfo:inlinefo:inline-containerfo:instream-foreign-objectfo:layout-master-setfo:leaderfo:list-blockfo:list-itemfo:list-item-bodyfo:list-item-labelfo:markerfo:multi-casefo:multi-propertiesfo:multi-property-setfo:multi-switchfo:multi-togglefo:page-numberfo:page-number-citationfo:page-sequencefo:page-sequence-masterfo:region-afterfo:region-beforefo:region-bodyfo:region-endfo:region-startfo:repeatable-page-master-alternativesfo:repeatable-page-master-referencefo:retrieve-markerfo:rootfo:simple-page-masterfo:single-page-master-referencefo:static-contentfo:tablefo:table-and-captionfo:table-bodyfo:table-captionfo:table-cellfo:table-columnfo:table-footerfo:table-headerfo:table-rowfo:titlefo:wrapperThe XSL formatting model is based on rectangular boxes called areas that can contain text, empty space, images, or other formatting objects. As with CSS boxes, an area has borders and padding on each of its sides, although CSS's margins are replaced by XSL's space-before and space-after. An XSL formatter reads the formatting objects to determine which areas to place where on the page. Many formatting objects produce single areas (at least most of the time);` but because of page breaks, word wrapping, hyphenation, and other details that must be taken into account when fitting a potentially infinite amount of text into a finite amount of space, some formatting objects do occasionally generate more than one area.

The

formatting objects differ primarily in what they represent. For

example, the fo:list-item-label formatting object is

a box that contains a bullet, a number, or another indicator placed

in front of a list item. A fo:list-item-body

formatting object is a box that contains the text, sans label, of the

list item. And a fo:list-item formatting object is a

box that contains both the fo:list-item-label and

fo:list-item-body formatting objects.

When processed, the formatting objects document is broken up into pages. A Web browser window will normally be treated as one very long page. A print format will often contain many individual pages. Each page contains a number of areas. There are four primary kinds of areas:

1. regions

2. block areas

3. line areas

4. inline areas

These form a rough hierarchy. Regions contain block areas. Block areas contain other block areas, line areas, and content. Line areas contain inline areas. Inline areas contain other inline areas and content. More specifically:

A region is the highest-level container in

XSL-FO. You can think of a page of this book as containing three

regions: the header, the main body of the page, and the footer.

Formatting objects that produce regions include fo:region-body,

fo:region-before, fo:region-after,

fo:region-start, and fo:region-end.

A block area represents a block-level

element, such as a paragraph or a list item. Although block areas may

contain other block areas, there should always be a line break before

the start and after the end of each block area. A block area, rather

than being precisely positioned by coordinates, is placed

sequentially in the area that contains it. As other block areas are

added and deleted before it or within it, the block area’s

position shifts as necessary to make room. A block area may contain

parsed character data, inline areas, line areas, and other block

areas that are sequentially arranged in the containing block area.

Formatting objects that produce block areas include fo:block,

fo:table-and-caption, and fo:list-block.

A line area represents a line of text inside a block. For example, each of the lines in this list item is a line area. Line areas can contain inline areas and inline spaces. There are no formatting objects that correspond to line areas. Instead, the formatting engine calculates the line areas as it decides how to wrap lines inside block areas.

Inline areas are parts of a line such as a

single character, a footnote reference, or a mathematical equation.

Inline areas can contain other inline areas and raw text. Formatting

objects that produce inline areas include fo:character,

fo:external-graphic, fo:inline,

fo:instream-foreign-object, fo:leader,

and fo:page-number.

When taken as a whole, the various formatting objects in an XSL-FO document specify the order in which content is to be placed on pages. However, formatting properties specify the details of formatting such as size, position, font, color, and a lot more. Formatting properties are represented as attributes on the individual formatting object elements.

The

details of many of these properties should be familiar from CSS. Work

is ongoing to ensure that CSS and XSL-FO use the same names to mean

the same things. For example, the CSS font-family

property means the same thing as the XSL font-family

property; and although the syntax for assigning values to properties

is different in CSS and XSL-FO, the meaning of the values themselves

is the same. To indicate that the fo:block element

is formatted in some approximation of Times, you might use this CSS

rule:

fo:block {font-family: 'New York', 'Times New Roman', serif}

The XSL-FO equivalent is to include a

font-family attribute in the fo:block

start tag in this way:

<fo:block font-family="'New York', 'Times New Roman', serif">

Although this is superficially different, the

style name (font-family) and the style value ('New

York', 'Times New

Roman', serif) are the same. CSS's

font-family property is specified as a list of font

names, separated by commas, in order from first choice to last

choice. XSL-FO’s font-family property is

specified as a list of font names, separated by commas, in order from

first choice to last choice. Both CSS and XSL-FO quote font names

that contain white space. Both CSS and XSL-FO understand the keyword

serif to mean an arbitrary serif font.

Of

course, XSL formatting objects support many properties that have no

CSS equivalent, such as destination-placement-offset,

block-progression-dimension, character,

and hyphenation-keep. You need to learn these to

take full advantage of XSL. The standard XSL-FO properties follow:

absolute-positionactive-statealignment-adjustalignment-baselineauto-restoreazimuthbackgroundbackground-attachmentbackground-colorbackground-imagebackground-positionbackground-position-horizontalbackground-position-verticalbackground-repeatbaseline-shiftblank-or-not-blankblock-progression-dimensionborderborder-after-colorborder-after-precedenceborder-after-styleborder-after-widthborder-before-colorborder-before-precedenceborder-before-styleborder-before-widthborder-bottomborder-bottom-colorborder-bottom-styleborder-bottom-widthborder-collapseborder-colorborder-end-colorborder-end-precedenceborder-end-styleborder-end-widthborder-leftborder-left-colorborder-left-styleborder-left-widthborder-rightborder-right-colorborder-right-styleborder-right-widthborder-separationborder-spacingborder-start-colorborder-start-precedenceborder-start-styleborder-start-widthborder-styleborder-topborder-top-colorborder-top-styleborder-top-widthborder-widthbottombreak-afterbreak-beforecaption-sidecase-namecase-titlecharacterclearclipcolorcolor-profile-namecolumn-countcolumn-gapcolumn-numbercolumn-widthcontent-heightcontent-typecontent-widthcountrycuecue-aftercue-beforedestination-placement-offsetdirectiondisplay-aligndominant-baselineelevationempty-cellsend-indentends-rowextentexternal-destinationfloatflow-namefontfont-familyfont-selection-strategyfont-sizefont-size-adjustfont-stretchfont-stylefont-variantfont-weightforce-page-countformatglyph-orientation-horizontalglyph-orientation-verticalgrouping-separatorgrouping-sizeheighthyphenatehyphenation-characterhyphenation-keephyphenation-ladder-counthyphenation-push-character-counthyphenation-remain-character-countidindicate-destinationinitial-page-numberinline-progression-dimensioninternal-destinationkeep-togetherkeep-with-nextkeep-with-previouslanguagelast-line-end-indentleader-alignmentleader-lengthleader-patternleader-pattern-widthleftletter-spacingletter-valuelinefeed-treatmentline-heightline-height-shift-adjustmentline-stacking-strategymarginmargin-bottommargin-leftmargin-rightmargin-topmarker-class-namemaster-namemaster-referencemax-heightmaximum-repeatsmax-widthmedia-usagemin-heightmin-widthnumber-columns-repeatednumber-columns-spannednumber-rows-spannedodd-or-evenorphansoverflowpaddingpadding-afterpadding-beforepadding-bottompadding-endpadding-leftpadding-rightpadding-startpadding-toppage-break-afterpage-break-beforepage-break-insidepage-heightpage-positionpage-widthpausepause-afterpause-beforepitchpitch-rangeplay-duringpositionprecedenceprovisional-distance-between-startsprovisional-label-separationreference-orientationref-idregion-namerelative-alignrelative-positionrendering-intentretrieve-boundaryretrieve-class-nameretrieve-positionrichnessrightrolerule-stylerule-thicknessscalingscaling-methodscore-spacesscriptshow-destinationsizesource-documentspace-afterspace-beforespace-endspace-startspace-treatmentspanspeakspeak-headerspeak-numeralspeak-punctuationspeech-ratesrcstart-indentstarting-statestarts-rowstresssuppress-at-line-breakswitch-totable-layouttable-omit-footer-at-breaktable-omit-header-at-breaktarget-presentation-contexttarget-processing-contexttarget-stylesheettext-aligntext-align-lasttext-altitudetext-decorationtext-depthtext-indenttext-shadowtext-transformtoptreat-as-word-spaceunicode-bidivertical-alignvisibilityvoice-familyvolumewhite-spacewhite-space-collapsewidowswidthword-spacingwrap-optionwriting-modexml:langz-indexXSL-FO is a complete XML vocabulary for laying out text on a page. An XSL-FO document is simply a well-formed XML document that uses this vocabulary. That means it has an XML declaration, a root element, child elements, and so forth. It must adhere to all the well-formedness rules of any XML document, or formatters will not accept it. By convention, a file that contains XSL formatting objects has the three-letter extension .fob or the two-letter extension .fo. However, it might have the suffix .xml because it also is a well-formed XML file.

Listing

19-1 is a simple document marked up using XSL formatting objects. The

root of the document is fo:root. This element

contains a fo:layout-master-set and a

fo:page-sequence. The fo:layout-master-set

element contains fo:simple-page-master child

elements. Each fo:simple-page-master describes a

kind of page on which content will be placed. Here there's only one

very simple page, but more complex documents can have different

master pages for first, right, and left, body pages, front matter,

back matter, and more, each with a potentially different set of

margins, page numbering, and other features. The name bu which the

page master will be referred to is given in the master-name

attribute.

Content

is placed on copies of the master page using a fo:page-sequence.

The fo:page-sequence has a master-reference

attribute naming the master page to be used. Its fo:flow

child element holds the actual content to be placed on the pages. The

content here is given as two fo:block children, each

with a font-size property of 20 points, a

font-family property of serif, and

a line-height of 30 points.

Listing 19-1 A simple XSL-FO document

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="only">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="only">

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<fo:block font-size="20pt" font-family="serif"

line-height="30pt">

Hydrogen

</fo:block>

<fo:block font-size="20pt" font-family="serif"

line-height="30pt" >

Helium

</fo:block>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>Although you could write a document such as Listing 19-1 by hand, doing so would lose all the benefits of content-format independence achieved by XML. Normally, you write an XSLT style sheet that transforms an XML source document into XSL-FO. Listing 19-2 is the XSLT style sheet that produced Listing 19-1 by transforming the previous chapter’s Listing 17-1.

Listing 19-2 A transformation from a source vocabulary to XSL formatting objects

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:output indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="only">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="only">

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block font-size="20pt" font-family="serif"

line-height="30pt">

<xsl:value-of select="NAME"/>

</fo:block>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>At

the time of this writing, no browser can directly display XML

documents transformed into XSL formatting objects. However, there are

several applications that can convert an XSL-FO document into a

viewable format such as PDF or TeX. The one used here is the XML

Apache project's open source FOP. FOP is a command-line Java program

that converts FO (formatting object) documents to Adobe Acrobat PDF

files. At the time of this writing, the most recent version of FOP is

0.20.4, which incompletely supports a subset of the formatting

objects and properties in the XSL 1.0 Recommendation. You can

download the latest version of FOP from http://xml.apache.org/fop/.

On the CD-ROM

FOP is included on the CD-ROM in the directory utilities/fop. However, chances are good that a version that supports XSL-FO more completely will have been released by the time you're reading this, so you should try to get it from the Web if you can.

FOP is a Java program that should run on any platform with a reasonably compatible Java 1.2 virtual machine. To install it, just unpack the distribution and add the directory where you put it (I use /usr/local/xml/fop) to your path.

The

directory where you installed it contains, among other files, fop.bat

and fop.sh. Use fop.bat for Windows and fop.sh for Unix. other

platforms can run the Java program directly by adding its JAR

archives to your CLASSPATH and invoking the org.apache.fop.apps.Fop

class. Run it from the command line with arguments specifying the

input and output files. For example,

C:\> fop.bat -fo 19-1.fo -pdf 19-1.pdf

The output will look something like this:

[INFO] FOP 0.20.4 [INFO] building formatting object tree [INFO] [1] [INFO] Parsing of document complete, stopping renderer

Here 19-1.fo is the input XML file that uses the formatting object vocabulary. 19-1.pdf is the output PDF file that can be displayed and printed by Adobe Acrobat or other programs that read PDF files.

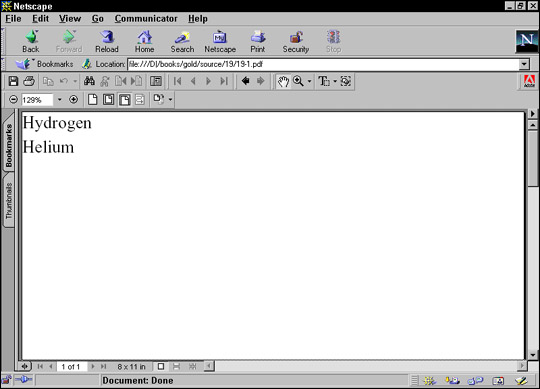

Although PDF files are themselves ASCII text, this isn’t a book about PostScript, so there’s nothing to be gained by showing you the exact output of the above command. If you’re curious, open the PDF file in any text editor. Instead, Figure 19-1 shows the rendered file displayed in Netscape Navigator using the Acrobat plug-in.

Figure 19-1: The PDF file displayed in Netscape Navigator

PDF files are not the only or even the primary eventual destination format for XML documents styled with XSL formatting objects. Certainly, one would hope that Web browsers will directly support XSL formatting objects in the not too distant future. For now, PDF files are the only convenient format, so that’s what I show in this chapter. Eventually, more software will be able to read and display these files.

The

root element of a formatting objects document is fo:root.

This element contains one fo:layout-master-set

element and one or more fo:page-sequence elements.

The fo:page-sequence elements contain content; that

is, text and images to be placed on the pages. The

fo:layout-master-set contains templates for the

pages that will be created. When the formatter reads an XSL-FO

document, it creates a page based on the first template in the

fo:layout-master-set. Then it fills it with content

from the fo:page-sequence. When it's filled the

first page, it instantiates a second page based on a template, and

fills it with content. The process continues until the formatter runs

out of content.

The

fo:root element generally has an xmlns:fo

attribute with the value http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format

and may (though it generally does not) have an id

attribute. The fo:root element exists just to

declare the namespace and be the document root. It has no direct

effect on page layout or formatting.

The

page templates are called page masters. Page masters are

similar in purpose to QuarkXPress master pages or PowerPoint slide

masters. Each defines a general layout for a page including its

margins, the sizes of the header, footer, and body area of the page,

and so forth. Each actual page in the rendered document is based on

one master page, and inherits certain properties like margins, page

numbering, and layout from that master page. XSL-FO 1.0 defines

exactly one kind of page master, the fo:simple-page-master,

which represents a rectangular page. The fo:layout-master-set

contains one or more fo:simple-page-master elements

that define master pages.

Note

Future versions of XSL-FO will add other kinds of page masters, possibly including non-rectangular pages.

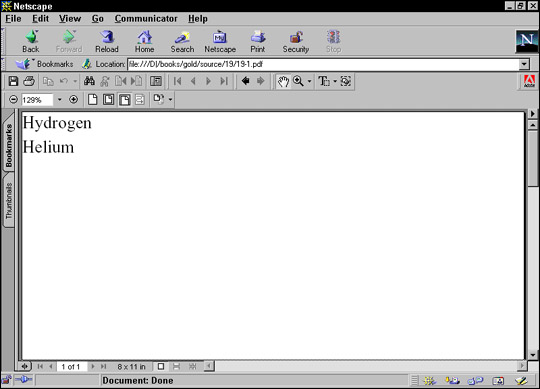

Each

master page is represented by a fo:simple-page-master

element. A fo:simple-page-master element defines a

page layout, including the size of its before region, body region,

after region, end region, and start region. Figure 19-2 shows the

typical layout of these parts. One thing that may not be obvious from

this picture is that the body region overlaps the other four regions

(though not the page margins); that is, the body is everything inside

the thick black line including the start, end, before, and after

regions.

Figure 19-2: The layout of the parts of a simple page of English text

Note

In normal English text, the end region is the right side of the page and the start region is the left side of the page. This is reversed in Hebrew or Arabic text, because these languages are written from right to left. In almost all modern languages, the before region is the header and the after region is the footer, but this could be reversed in a language that wrote from bottom to top.

The

fo:simple-page-master element has three main

attributes:

master-name: the name by

which page sequences will reference this master page

page-height: the height of

the page

page-width: the width of the

page

If

the page-height and page-width are

not provided, then the formatter chooses a reasonable default based

on the media in use (for example, 8.5" × 11").

Other attributes commonly applied to page masters include:

The margin-bottom,

margin-left, margin-right, and

margin-top attributes, or the shorthand margin

attribute

The writing-mode attribute

that determines which direction text flows on the page, for example,

left-to-right or right-to-left or top-to-bottom

The reference-orientation

attribute that specifies in 90-degree increments whether and how much

the content is rotated

For

example, here is a fo:layout-master-set containing

one fo:simple-page-master named US-Letter.

It specifies an 8.5 × 11-inch page with half-inch margins on

each side. It contains a single region, the body, into which all

content will be placed.

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="US-Letter"

page-height="11in" page-width="8.5in"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>The

designer sets the size of the body (center) region, header, footer,

end region, and start region, as well as the distances between them,

by adding region child elements to the fo:simple-page-master.

These are:

fo:region-before

fo:region-after

fo:region-body

fo:region-start

fo:region-end

The

fo:region-before and fo:region-after

elements each have an extent attribute that gives

the height of these regions. Their width extends from the left side

of the page to the right side. The fo:region-start

and fo:region-end elements each have an extent

attribute that specifies their widths. Their height extends from the

bottom of the start region to the top of the end region. (This

assumes normal Western text. Details would be rotated in Chinese or

Hebrew or some other non-right-to-left-top-to-bottom

script.)

The

fo:region-body does not have an extent

attribute. Instead, the size of the body is everything inside the

page margins. Thus, the region body overlaps the other four regions

on the page. If you place text into the body and the other four

regions, text will be drawn on top of other content. To avoid this,

you must set the left margin of the body to be as large or larger

than the extent of the start region, the top margin of the body to be

as large or larger than the extent of the before region, and so on.

Each

of the five regions of a simple page master may be filled with

content from a fo:flow or fo:static-content

element when the document is processed. However, these elements do

not contain that content. Instead, they simply give the dimensions of

the boxes the formatter will build to put content in. They are

blueprints for the boxes, not the boxes themselves.

For

example, this fo:simple-page-master creates pages

with one-inch before and after regions. The region body will extend

vertically from the bottom of the before region to the top of the

after region. It will extend horizontally from the left side of the

page to the right side of the page because there is no start or end

region.

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="table_page">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in" margin-bottom="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-after extent="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

For another example, here is a

fo:layout-master-set that makes all outer regions

one inch. Furthermore, the page itself has a half-inch margin on all

sides.

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="only"

page-width="8.5in" page-height="11in"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-start extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-end extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-after extent="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>The body regions from pages based on this page master will be 5.5 inches wide and 8 inches high. That's calculated by subtracting the sum of the body region's margins and the page margins from the size of the page.

In

addition to a fo:layout-master-set, each formatting

object document contains one or more fo:page-sequence

elements. Each page in the sequence has an associated page master

that defines how the page will look. Which page master this is, is

determined by the master-reference attribute of the

fo:page-sequence element. This must match the name

of a page master in the fo:layout-master-set.

Listing 19-1 used a fo:simple-master-page named only

to fill this role, but it is not uncommon to have more than one

master page. In this case, the master pages might be grouped as part

of a fo:page-sequence-master instead. For instance,

you could have one master page for the first page of each chapter, a

different one for all the subsequent left-hand pages, and a third for

all the subsequent right-hand pages. Or, there could be one simple

page master for a table of contents, another for body text, and a

third for the index. In this case, you use one page sequence each for

the table of contents, the body text, and the index.

Each page sequence contains three child elements in this order:

1. An optional fo:title

element containing inline content that can be used as the title of

the document. This would normally be placed in the title bar of the

browser window like the TITLE element in HTML

2. Zero or more fo:static-content

elements containing text to be placed on every page

3. One fo:flow element

containing data to be placed on each page in turn

The

main difference between a fo:flow and a

fo:static-content is that text from the flow isn't

placed on more than one page, whereas the static content is. For

example, the words you're reading now are flow content that only

appear on this page, whereas the part and chapter titles at the top

of the page are static content that is repeated from page to page.

The

fo:flow element contains, in order, the elements to

be placed on the page. As each page fills with elements from the

flow, a new page is created with the next master page in the page

sequence master for the elements that remain in the flow. With a

simple page master, the same page will be instantiated repeatedly, as

many times as necessary to hold all the content.

The

fo:static-content element contains information to be

placed on each page. For instance, it may place the title of a book

in the header of each page. Static content can be adjusted depending

on the master page. For instance, the part title may be placed on

left-hand pages, and the chapter title on right-hand pages. The

fo:static-content element can also be used for items

such as page numbers that have to be calculated from page to page. In

other words, what's static is not the text, but the calculation that

produces the text.

The

fo:flow object holds the actual content, which will

be placed on the instances of the master pages. This content is

composed of a sequence of fo:block,

fo:block-container, fo:table-and-caption,

fo:table, and fo:list-block

elements. This section sticks to basic fo:block

elements, which are roughly equivalent HTML's DIV

elements. Later in this chapter, you learn more block-level elements

that a flow can contain.

For example, here is a basic flow containing the names of several atoms, each in its own block:

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body"> <fo:block>Actinium</fo:block> <fo:block>Aluminum</fo:block> <fo:block>Americium</fo:block> </fo:flow>

The flow-name attribute of the

fo:flow, here with the value xsl-region-body,

specifies which of the five regions of the page this flow's content

will be placed in. The allowed values are:

xsl-region-body

xsl-region-before

xsl-region-after

xsl-region-start

xsl-region-end

For example, a flow for the header has a flow-name value of xsl-region-before. A flow for the body would have a flow-name of xsl-region-body.

Only one fo:flow is allowed in the same page sequence.

The other four regions have to be filled with a fo:static-content if anything.

You

can now put together a complete style sheet that lays out the entire

periodic table. Listing 19-3 demonstrates this with an XSLT style

sheet that converts the periodic table into XSL formatting objects.

The flow grabs all the atoms and places each one in its own block. A

simple page master named only defines an A4-sized

master page in landscape mode with half-inch margins on each side.

Listing 19-3 A basic style sheet for the periodic table

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4">

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

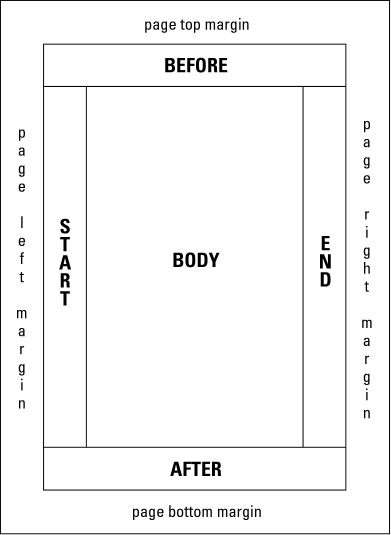

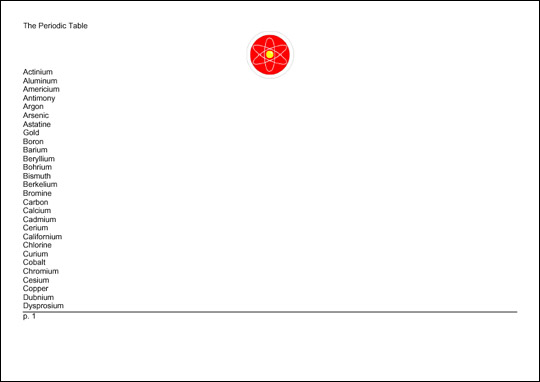

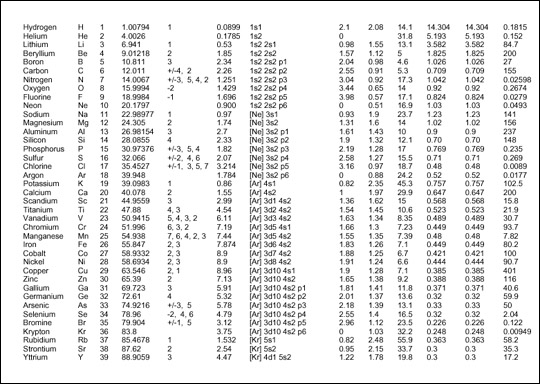

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-3 shows the resulting document after Listing 19-3 has been run through an XSLT processor to produce an XSL-FO document, and that document has been run through FOP to produce a PDF file.

Figure 19-3: The output of Listing 19-3

Whereas

each piece of the content of a fo:flow element

appears on one page, each piece of the content of a fo:static-content

element appears on every page. For instance, if this book were laid

out in XSL-FO, then both the header at the top of the page and the

footer at the bottom of the page would have been produced by

fo:static-content elements. You do not have to use

fo:static-content elements, but if you do use them

they must appear before all the fo:flow elements in

the page sequence.

fo:static-content

elements have the same attributes and contents as a fo:flow.

However, because a fo:static-content cannot break

its contents across multiple pages if necessary, it generally has

less content than a fo:flow. For example, Listing

19-4 uses a fo:static-content to place the words

"The Periodic Table" in the header of each page.

Listing 19-4 Using fo:static-content to generate a header

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4">

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-before">

<fo:block>The Periodic Table</fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

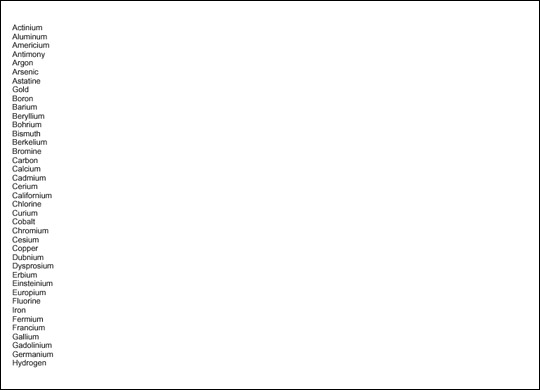

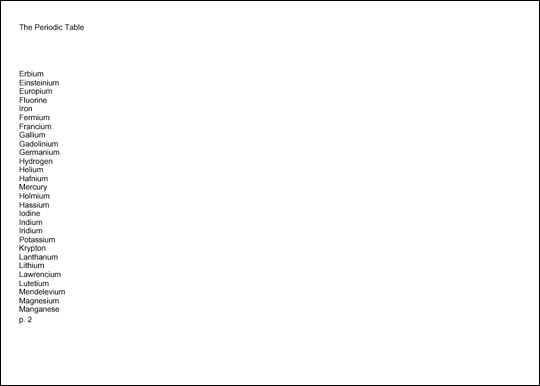

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-4 shows the last page of the PDF file ultimately produced by Listing 19-4. The same text, "The Periodic Table", appears on all four pages of the document.

Figure 19-4: Static content in the header

The

fo:page-sequence element has eight optional

attributes that define page numbers for the sequence. These are:

initial-page-number

force-page-count

format

letter-value

country

language

grouping-separator

grouping-size

The

initial-page-number attribute gives the number of

the first page in this sequence. The most likely value for this

attribute is 1, but it could be a larger number if the previous pages

are in a different fo:page-sequence or even a

different document. It can also be set to one of these three key

words:

auto: 1 unless pages from a

preceding fo:page-sequence have pushed that up. This

is the default.

auto-odd: Same as auto,

but add 1 if that value is an even number; that is, start on an odd

page.

auto-even: Same as auto,

but add 1 if that value is an odd number; that is, start on an even

page.

The

force-page-count attribute is used to require the

document to have an even or odd number of pages or to end on an even

or odd page. This is sometimes necessary for printed books. The

force-page-count attribute can have one of these six

keyword values:

auto: Make the last page an

odd page if the initial-page-number of the next

fo:page-sequence is even. Make the last page an

even-page if the initial-page-number of the next page-sequence is

odd. If there is no next fo:page-sequence or if the

next fo:page-sequence does not specify an

initial-page-number, then let the last page fall

where it may.

even: Require an even number

of pages, inserting an extra blank page if necessary to make it so.

odd: Require an odd number

of pages, inserting an extra blank page if necessary to make it so.

end-on-even: Require the

last page to have an even page number, inserting an extra blank page

if necessary to make it so.

end-on-odd: Require the last

page to have an odd page number, inserting an extra blank page if

necessary to make it so.

no-force: Do not require

either an even or odd number of pages.

The

country attribute should be set to an RFC 1766

country code. The language attribute should be set

to an RFC 1766 language code (http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1766.txt).

For instance, you would use en to indicate English

and us to indicate the United States.

Cross-Reference

These are

essentially the same as the legal values for xml:lang

that were discussed in Chapter 11, except that the country code and

language codes are placed in two separate attributes rather than in

one attribute.

The

remaining four attributes have exactly the same syntax and meaning as

when used as attributes of the xsl:number element

from XSLT, so I won't repeat that discussion here.

Cross-Reference

The xsl:number

element and the format, letter-value,

grouping-separator, and grouping-size

attributes are discussed in the "Number to String Conversion"

section in Chapter 18.

The

fo:page-number formatting object is an empty inline

element that inserts the number of the current page. The formatter is

responsible for determining what that number is. This element can

have a variety of formatting attributes common to inline elements

such as font-family and text-decoration.

For example, Listing 19-5 uses fo:static-content and

fo:page-number to put the page number at the bottom

of every page:

Listing 19-5 Using fo:page-number to place the page number in the footer

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in"

margin-bottom="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-after extent="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4"

initial-page-number="1" language="en" country="us">

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-before">

<fo:block>The Periodic Table</fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-after">

<fo:block>p. <fo:page-number/></fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

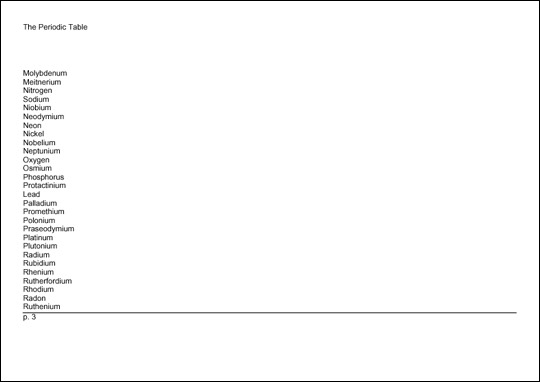

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-5 shows the second page of the PDF file generated from Listing 19-5. The page number appears at the bottom of this and every other page in the document.

Figure 19-5: Automatically generated page numbers in the footer

Each

page the formatter creates is associated with a master page from the

fo:layout-master-set that defines how the page will

look. Which master page this is, is determined by the

master-reference attribute of the fo:page-sequence

element. Listing 19-3 through 19-5 used a single

fo:simple-master-page named A4 to

fill this role, but it is not uncommon to have more than one master

page. For instance, you could use one master page for the first page

of each chapter, a different one for all the subsequent left-hand

pages, and a third for all the subsequent right-hand pages. In this

case, the master pages might be grouped as part of a

fo:page-sequence-master instead.

The

fo:page-sequence-master element is a child of the

fo:layout-master-set that lists the order in which

particular master pages will be instantiated using one or more of

these three child elements:

fo:single-page-master-reference

fo:repeatable-page-master-reference

fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives

The

fo:single-page-master-reference

and fo:repeatable-page-master-reference elements

each have a master-reference attribute that

specifies which fo:simple-master-page their pages

are based on. The fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives

has child fo:conditional-page-master-reference

elements that are instantiated based on various conditions. Each of

these child fo:conditional-page-master-reference

elements has a master-reference

attribute that specifies which fo:simple-master-page

to use if its condition is satisfied.

The

simplest is fo:single-page-master-reference whose

master-reference attribute identifies one master

page to be instantiated. For example, this fo:layout-master-set

contains a fo:page-sequence-master element named

contents that says that all text should be placed on

a single instance of the master page named A4:

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents">

<fo:single-page-master-reference master-reference="A4"/>

</fo:page-sequence-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>This page sequence master only allows the creation of a single page. Technically, it's an error if there's more content than can fit on this one page. However, in practice most formatters simply repeat the last page used until they have enough pages to hold all the content.

Now consider this page sequence master:

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents"> <fo:single-page-master-reference master-name="A4"/> <fo:single-page-master-reference master-name="A4"/> </fo:page-sequence-master>

This provides for up to two pages, each based

on the master page named A4. If the first page fills

up, a second is created. If that page fills up, then the formatter

may throw an error, or it may create extra pages.

The

same technique can be used to apply different master pages. For

example, this sequence specification bases the first page on the

master page named front and the second on the master

page named back:

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents"> <fo:single-page-master-reference master-reference="front"/> <fo:single-page-master-reference master-reference="back"/> </fo:page-sequence-master>

The first page the formatter creates will be based on the master page named front. The second page created will be based on the master page named back. If the second page fills up, the formatter may throw an error; or it may create extra pages based on back, the last master page instantiated.

Of

course, you usually don't know in advance exactly how many pages

there will be. The fo:repeatable-page-master-reference

element lets you specify that as many pages as necessary will be used

to hold the content, all based on a single master page. The

master-reference attribute identifies which master

page will be repeated. For example, this page sequence master will

use as many copies of the master page named A4 as

necessary to hold all the content:

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents"> <fo:repeatable-page-master-reference master-reference="A4"/> </fo:page-sequence-master>

Alternately, you can set the maximum-repeats

attribute of the fo:repeatable-page-master-reference

element to limit the number of pages that will be created. For

instance, this fo:page-sequence-master generates at

most 10 pages per document:

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents">

<fo:repeatable-page-master-reference master-reference="A4"

maximum-repeats="10"/>

</fo:page-sequence-master>This also lets you do things like using one master for the first two pages, another for the next three pages, and a third master for the next 10 pages.

The

fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives element

specifies different master pages for the first page, even pages, odd

pages, blank pages, last even page, and last odd page. This is more

designed for a chapter of a printed book where the first and last

pages, as well the even and odd pages, traditionally have different

margins, headers, and footers.

Because

a fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives element

needs to refer to more than one master page, it can't use a

master-reference attribute such as

fo:single-page-master-reference and

fo:repeatable-page-master-reference. Instead, it has

fo:conditional-page-master-reference child elements.

Each of these has a master-reference attribute that

identifies the master page to instantiate given that condition. The

conditions themselves are determined by three attributes:

page-position: This

attribute can be set to first, last,

rest, or any to identify it as

applying only to the first page, last page, any page except the

first, or any page respectively.

odd-or-even: This attribute

can be set to odd, even, or any

to identify it as applying only to odd pages, only to even pages, or

to all pages respectively.

blank-or-not-blank: This

attribute can be set to blank, not-blank,

or any to identify it as applying only to blank

pages, only to pages that contain content, or to all pages

respectively.

For

example, this page sequence master says that the first page should be

based on the master page named letter_first but that

all subsequent pages should use the master page named letter:

<fo:page-sequence-master master-name="contents">

<fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives>

<fo:conditional-page-master-reference

page-position="first" master-reference="letter_first"/>

<fo:conditional-page-master-reference

page-position="rest" master-reference="letter"/>

</fo:repeatable-page-master-alternatives>

</fo:page-sequence-master master-reference="contents">If the content overflows the first page, the remainder will be placed on a second page. If it overflows the second page, a third page will be created. As many pages as needed to hold all the content will be constructed.

The

content (as opposed to markup) of an XSL-FO document is mostly text.

Non-XML content such as GIF and JPEG images can be included in a

fashion similar to the IMG element of HTML. Other

forms of XML content, such as MathML and SVG, can be embedded

directly inside the XSL-FO document. This content is stored in

several kinds of elements including:

Block-level formatting objects

Inline formatting objects

Table formatting objects

Out-of-line formatting objects

All

of these different kinds of elements are descendants of either a

fo:flow or a fo:static-content

element. They are never placed directly on page masters or page

sequences.

A block-level formatting object is drawn as a rectangular area separated by a line break and possibly extra white space from any content that precedes or follows it. Blocks may contain other blocks, in which case the contained blocks are also separated from the containing block by a line break and perhaps extra white space. Block-level formatting objects include:

fo:block

fo:block-container

fo:table-and-caption

fo:table

fo:list-block

The

fo:block element is the XSL-FO equivalent of

display: block in CSS or DIV in

HTML. Blocks may be contained in fo:flow elements,

other fo:block elements, and fo:static-content

elements. fo:block elements may contain other

fo:block elements, other block-level elements such

as fo:table and fo:list-block, and

inline elements such as fo:inline and

fo:page-number. Block-level elements may also

contain raw text. For example:

<fo:block>The Periodic Table, Page <fo:page-number/></fo:block>

The block-level elements generally have attributes for both area properties and text-formatting properties. The text-formatting properties are inherited by any child elements of the block unless overridden.

Caution

As of version

0.20.4, FOP does not support fo:block-container or

fo:table-and-caption.

An inline formatting object is also drawn as a rectangular area that may contain text or other inline areas. However, inline areas are most commonly arranged in lines running from left to right. When a line fills up, a new line is started below the previous one. The exact order in which inline elements are placed depends on the writing mode. For example, when working in Hebrew or Arabic, inline elements are first placed on the right and then fill to the left. Inline formatting objects include:

fo:bidi-override

fo:character

fo:external-graphic

fo:initial-property-set

fo:instream-foreign-object

fo:inline

fo:inline-container

fo:leader

fo:page-number

fo:page-number-citation

Caution

As of version

0.20.4, FOP does not support fo:bidi-override,

fo:initial-property-set, or fo:inline-container.

The

table formatting objects are the XSL-FO equivalents of CSS2 table

properties. However, tables do work somewhat more naturally in XSL-FO

than in CSS. For the most part, an individual table is a block-level

object, while the parts of the table aren't really either inline or

block level. However, an entire table can be turned into an inline

object by wrapping it in a fo:inline-container.

There are nine XSL table formatting objects:

fo:table-and-caption

fo:table

fo:table-caption

fo:table-column

fo:table-header

fo:table-footer

fo:table-body

fo:table-row

fo:table-cell

The

root of a table is either a fo:table or a

fo:table-and-caption that contains a fo:table

and a fo:caption. The fo:table

contains a fo:table-header, fo:table-body,

and fo:table-footer. The table body contains

fo:table-row elements that are divided up into

fo:table-cell elements.

Caution

FOP 0.20.4 has

limited support for the table formatting objects, and none at all for

fo:table-and-caption and fo:table-caption.

There are three "out-of-line" formatting objects:

fo:float

fo:footnote

fo:footnote-body

Out-of-line formatting objects "borrow" space from existing inline or block objects. On the page, they do not necessarily appear between the same elements that they appeared between in the input formatting object XML tree.

Caution

FOP 0.20.4 does

not support fo:float.

A

rule is a block-level horizontal line inserted into text similar to

the line below the chapter title on the first page of this chapter.

The HR element in HTML produces a rule. A leader is

a line that extends from the right side of left-aligned text in the

middle of a line to the left side of some right-aligned text on the

same line. It's most commonly made up of dots, although other

characters can be used. Leaders are commonly seen in menus and tables

of contents. In fact, if you flip back to the table of contents at

the beginning of this book, you'll see leaders between chapter and

section titles and the page numbers.

In

XSL-FO both leaders and rules are produced by the fo:leader

element. This is an inline element that represents a leader, although

it can easily serve as a rule by placing it inside a fo:block.

Six attributes describe the appearance of a leader:

leader-alignment: This can

be set to reference-area or page to

indicate that the start edge of the leader should be aligned with the

start edge of the named item. It can also be set to none

or inherit.

leader-length: The length of

the leader, such as 12pc or 5in.

leader-pattern: This can be

set to space, rule, dots,

use-content, or inherit. The

use-content value means that the leader characters

should be read from the content of the fo:leader

element.

leader-pattern-width: This

property can be set to a specific length such as 2mm

or to use-font-metrics, which indicates that the

leader should simply be as big as it would naturally be. This is not

the length of the entire leader (which is set by leader-length);

it is the length of each repeating pattern in the leader. If

necessary, white space will be added to stretch each pattern out to

the requested length.

rule-style: This property

has the same values as the CSS border-style

properties; that is, none, dotted,

dashed, solid, double,

groove, ridge, and inherit.

rule-thickness: This

property is the thickness (width) of the rule; 1pt by default.

In

addition, a number of other common properties apply to leaders. For

instance, you can use the font-family property to

change the font in which a leader is drawn or the color

property to change the color in which a leader is drawn. For example,

this is a green horizontal line that’s 7.5 inches long and 2

points thick:

<fo:block>

<fo:leader leader-length="7.5in" leader-pattern="rule"

rule-thickness="2pt" color="green"/>

</fo:block>

Listing 19-6 uses fo:leader to

place a rule at the top of each page footer.

Listing 19-6 Using fo:leader to separate the footer from the body with a horizontal line

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in"

margin-bottom="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-after extent="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference`="A4"

initial-page-number="1" language="en" country="us">

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-before">

<fo:block>The Periodic Table</fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-after">

<fo:block><fo:leader leader-pattern="rule"

leader-length="18cm" />

</fo:block>

<fo:block>p. <fo:page-number/></fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-6 shows the third page of the PDF file generated from Listing 19-6. The rule appears at the bottom of this and every other page in the document.

Figure 19-6: Automatically generated rules in the footer

XSL-FO

provides two elements for embedding pictures in a rendered document.

The fo:external-graphic element inserts a non-XML

graphic, such as a JPEG image. The fo:instream-foreign-object

element inserts an XML document that is not an XSL-FO document, such

as an SVG picture or a MathML equation.

The

fo:external-graphic element provides the equivalent

of an HTML IMG element. That is, it loads an image,

probably in a non-XML format, from a URL. fo:external-graphic

is always an empty element with no children. The src

attribute contains a URI identifying the location of the image to be

embedded. For example, consider this standard HTML IMG

element:

<IMG SRC="cup.gif">

The fo:external-graphic

equivalent looks like this:

<fo:external-graphic src="cup.gif"/>

Of course, you can use an absolute URL if you like:

<fo:external-graphic

src="http://www.cafeconleche.org/cup.gif"/>Just as with Web browsers and HTML, there's no guarantee that any particular formatting engine recognizes and supports any particular graphic format. Currently, FOP supports GIF, JPEG, and SVG images. PNG is supported if you have Sun's JIMI library installed. More formats may be added in the future.

fo:external-graphic

is an inline element. You can make it a block-level picture simply by

wrapping it in a fo:block element like this:

<fo:block><fo:external-graphic src="cup.gif"/></fo:block>

Listing 19-7 shows a style sheet that loads the

image at http://www.cafeconleche.org/images/atom.jpg

and puts it in the header of all the pages. In this case, the URI of

the image is hard coded in the style sheet. In general, however, it

would be read from the input document.

Listing 19-7 An XSL style sheet that references an external graphic

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in"

margin-bottom="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-after extent="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4"

initial-page-number="1" language="en" country="us">

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-before">

<fo:block>

<fo:external-graphic

src="http://www.cafeconleche.org/images/atom.jpg"

/>

The Periodic Table

</fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-after">

<fo:block>

<fo:leader leader-pattern="rule"

leader-length="18cm"/>

</fo:block>

<fo:block>p. <fo:page-number/></fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

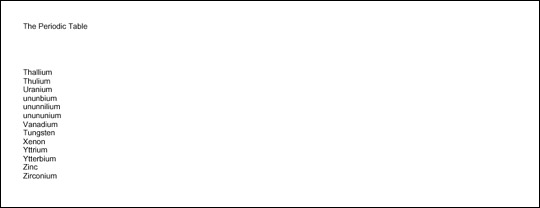

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-7 shows the first page of the PDF file generated from Listing 19-7. The picture appears at the top of this and every other page in the document.

Figure 19-7: Inserting an external graphic in the header

The

fo:instream-foreign-object inserts a graphic element

that is described in XML and that is included directly in the XSL-FO

document. For example, a fo:instream-foreign-object

element might contain an SVG picture. The formatter would render the

picture in the finished document. Listing 19-8 is an XSL-FO document

that places the pink triangle SVG example from Chapter 2 on the

header of each page:

Listing 19-8 An XSL style sheet that contains an instream SVG picture

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-before extent="1.0in"/>

<fo:region-body margin-top="1.0in"/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4"

initial-page-number="1" language="en" country="us">

<fo:static-content flow-name="xsl-region-before">

<fo:block> The Periodic Table

<fo:instream-foreign-object>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

width="1.5cm" height="1cm">

<polygon style="fill:#FFCCCC" points="0,31 18,0 36,31"/>

</svg>

</fo:instream-foreign-object>

</fo:block>

</fo:static-content>

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM"/>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:block><xsl:value-of select="NAME"/></fo:block>

</xsl:template>

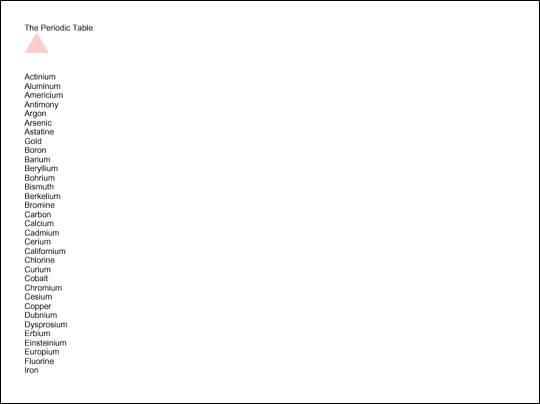

</xsl:stylesheet>Figure 19-8 shows the first page of the PDF file generated from Listing 19-8. The triangle appears at the top of this and every other page in the document.

Figure 19-8: Embedding an instream graphic in the header

Not all formatters support all possible XML graphics formats. For instance, FOP does not support MathML at all, and only supports a subset of SVG. Still this is a useful technique, especially when you want XSLT to generate pictures at runtime. For instance, you could write an XSLT style sheet that produced nicely formatted annual reports, including all the charts and graphics, simply by transforming some of the input document into XSL-FO and other parts of the input document into SVG.

fo:external-graphic

and fo:instream-foreign-object share a number of

properties designed to scale, position, crop, align, and otherwise

adjust the appearance of the image on the page.

The

content-type attribute specifies the type of the

graphic. You can give this as a MIME media type, such as image/jpg or

image/svg+xml, by prefixing the actual type with content-type:.

For example, to specify that the fo:external-graphic

element refers to a GIF image you would write it as

<fo:external-graphic content-type="content-type:image/gif"

src="cup.gif" />

This can also be given in terms of a namespace

prefix by using a value in the form namespace-prefix:prefix.

For example, to specify that the fo:instream-foreign-object

includes an SVG picture you write it as

<fo:instream-foreign-object xmlns:svg="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" content-type="namespace-prefix:svg">

The namespace prefix does not have to be

declared on the fo:instream-foreign-object element.

It simply needs to be declared somewhere in the ancestors of the

element.

The

height and width attributes specify

the vertical and horizontal size of the rectangle set aside on the

page for the image. Either or both of these can be set to the keyword

auto, rather than to an absolute length, to indicate

that the size of the image itself should be used.

The

content-height and content-width

attributes specify the vertical and horizontal size of the image

itself. If either or both of these is not the same as height

and width, respectively, then the image has to be

scaled.

The

scaling attribute can be set to either uniform

or non-uniform. Uniform scaling maintains the

height-to-width ratio of the image as it's scaled. This is the

default. Non-uniform scaling may scale the height and width

differently, so that the image is distorted.

You

can also choose the algorithm by which scaling occurs by using the

scaling-method attribute. This can be set to auto,

integer-pixels, or resample-any-method.

Integer scaling maintains an integral ratio between original and

scaled images such as 2:1 or 3:1, but not 1.5:1. In most cases,

integer-scaled images are smaller than images scaled by

resample-any-method, but won’t require

dithering. The value auto lets the formatter decide

what to do.

In

addition, you can set a variety of common properties for inline

elements. These include the common accessibility, aural, background,

border, padding, and margin properties. Because graphics shouldn't be

split across multiple pages, they don’t support the usual break

properties, but they do support keep-with-next and

keep-with-previous.

The

fo:basic-link element encodes HTML-style hyperlinks

in XSL-FO documents. This is an inline formatting object that the

user can click on to move to a different document, or to a different

place in the same document. This doesn’t offer much for print,

but it might be useful when and if Web browsers support XSL-FO

directly. The link behavior is controlled by these eight attributes:

external-destination

internal-destination

indicate-destination

show-destination

destination-placement-offset

target-presentation-context

target-processing-context

target-stylesheet

A

link to a remote document target specifies the URI through the value

of the external-destination attribute. The browser

should replace the current document with the document at this URI

when the reader activates the link. In most GUI environments, the

user activates the link by clicking on its contents. For example:

<fo:block> Be sure to visit the

<fo:basic-link

external-destination="http://www.cafeconleche.org/">

Cafe con Leche Web site!

</fo:basic-link>

</fo:block>

You can also link to another node in the same

document by using the internal-destination

attribute. The value of this attribute is not a URI, but rather the

ID of the element you're linking to. You can often use the

generate-id() function of XSLT to produce both the

IDs on the output elements and the links to those elements inside the

XSL-FO output. You should not specify both the internal and external

destination for one link.

The

three other destination attributes affect the appearance and behavior

of the link. The indicate-destination attribute has

a boolean value (true or false;

false by default) that specifies whether, when the

linked item is loaded, it should somehow be distinguished from

non-linked parts of the same document. For example, if you

follow a link to one ATOM element in a table of 100

atoms, the specific atom you were connecting to might be in boldface

while the other atoms are in normal type. The exact details are

system dependent.

The

show-destination attribute has two possible values:

replace (the default) and new. With

a value of replace, when a link is followed, the

target document replaces the existing document in the same window.

With a value of new, when the user activates a link,

the browser opens a new window in which to display the target

document.

When

a browser follows an HTML link into the middle of a document,

generally the specific linked element is positioned at the tip-top of

the window. The destination-placement-offset

attribute specifies how far down the browser should scroll the linked

element in the window. It's given as a length such as 3in

or 156px.

The

three target properties describe how the document at the other end of

the link will be displayed. The target-presentation-context

attribute contains a URI that generally indicates some subset of the

external destination that should actually be presented to the user.

For instance, an XPointer could be used here to say that although an

entire book is loaded only the seventh chapter will be shown.

The

target-processing-context attribute contains a URI

that serves as a base URI in the event that the external destination

contains a relative URI. Otherwise, that would be considered relative

to the current document.

Finally,

the target-stylesheet attribute contains a URI that

points to a style sheet that should be used when the targeted

document is rendered. This overrides any style sheet that the

targeted document itself specifies, whether through an xml-stylesheet

processing instruction, a LINK element in HTML, or

an HTTP header.

In addition, the link may have the usual accessibility, margin, background, border, padding, and aural properties.

The

fo:list-block formatting object element describes a

block-level list element. (There are no inline lists.) A list may or

may not be bulleted, numbered, indented, or otherwise formatted. Each

fo:list-block element contains either a series of

fo:list-item elements or fo:list-item-label

fo:list-item-body pairs. (It cannot contain both.) A

fo:list-item must contain a fo:list-item-label

and a fo:list-item-body. The fo:list-item-label

contains the bullet, number, or other label for the list item as a

block level element. The fo:list-item-body contains

block-level elements holding the actual content of the list item. To

summarize, a fo:list-block contains fo:list-item

elements. Each fo:list-item contains a

fo:list-item-label and fo:list-item-body.

However, the fo:list-item elements can be omitted.

For example:

<fo:list-block>

<fo:list-item>

<fo:list-item-label><fo:block>*</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body>

<fo:block>Actinium</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-body>

</fo:list-item>

<fo:list-item>

<fo:list-item-label><fo:block>*</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body>

<fo:block>Aluminum</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-body>

</fo:list-item>

</fo:list-block>

Or, with the fo:list-item tags

removed:

<fo:list-block>

<fo:list-item-label>

<fo:block>*</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body>

<fo:block>Actinium</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-body>

<fo:list-item-label>

<fo:block>*</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body>

<fo:block>Aluminum</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-body>

</fo:list-block>

The

fo:list-block element has two special attributes

that control list formatting:

provisional-label-separation:

The distance between the list item label and the list item body,

given as a triplet of maximum;minimum;optimum, such as

2mm;0.5mm;1mm.

provisional-distance-between-starts:

The distance between the start edge of the list item label and the

start edge of the list item body.

fo:list-block

also has the usual accessibility, aural, border, padding, background,

margin, and keeps and breaks properties. The fo:list-item

element has the standard block-level properties for backgrounds,

position, aural rendering, borders, padding, margins, line and page

breaking. The fo:list-item-label and

fo:list-item-body elements only have the

accessibility properties: id and keep-together.

The rest of their formatting is controlled either by the parent

elements (fo:list-item and fo:list-item-block)

or the child elements they contain.

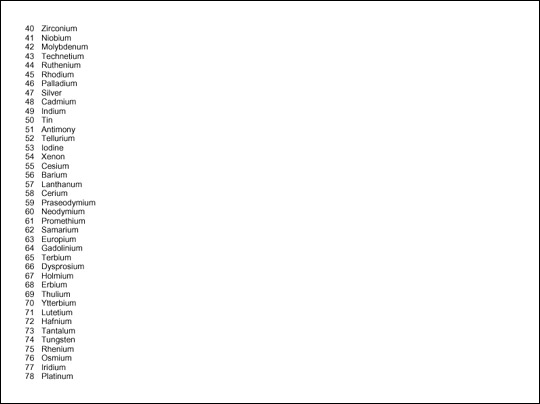

Listing 19-9 formats the periodic table as a list in which the atomic numbers are the list labels and the names of the elements are the list bodies. Figure 19-9 shows the second page of output produced by this style sheet.

Listing 19-9 An XSL style sheet that formats the periodic table as a list

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<xsl:template match="/">

<fo:root xmlns:fo="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Format">

<fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:simple-page-master master-name="A4"

page-width="297mm" page-height="210mm"

margin-top="0.5in" margin-bottom="0.5in"

margin-left="0.5in" margin-right="0.5in">

<fo:region-body/>

</fo:simple-page-master>

</fo:layout-master-set>

<fo:page-sequence master-reference="A4">

<fo:flow flow-name="xsl-region-body">

<fo:list-block>

<xsl:apply-templates select="//ATOM">

<xsl:sort data-type="number"

select="ATOMIC_NUMBER"/>

</xsl:apply-templates>

</fo:list-block>

</fo:flow>

</fo:page-sequence>

</fo:root>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:list-item>

<fo:list-item-label><fo:block>

<xsl:value-of select="ATOMIC_NUMBER"/>

</fo:block></fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body><fo:block>

<xsl:value-of select="NAME"/>

</fo:block></fo:list-item-body>

</fo:list-item>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Figure 19-9: The periodic table formatted as a list

In

HTML a list item implies a certain level of indenting. However, as

you can see in Figure 19-9, no such indenting is implied by any of

the XSL-FO list elements. If you want list items to be indented, you

can use the start-indent and end-indent

attributes on the fo:list-item-label and

fo:list-item-body elements. Each of these is set to

a length. However, because the list item body normally starts on the

same line as the list item label, its start indent is often given by

the special XSL-FO body-start() function. This

returns the combined length of the start-indent and

the provisional-distance-between-starts. For

example,

<xsl:template match="ATOM">

<fo:list-item>

<fo:list-item-label start-indent="1.0cm"

end-indent="1.0cm">

<fo:block>

<xsl:value-of select="ATOMIC_NUMBER"/>

</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-label>

<fo:list-item-body start-indent="body-start()">

<fo:block>

<xsl:value-of select="NAME"/>

</fo:block>

</fo:list-item-body>

</fo:list-item>

</xsl:template>

The

fundamental table element in XSL is fo:table-and-caption.

This is a block-level object that contains a fo:table

and a fo:caption. If your table doesn’t need a

caption, you can just use a raw fo:table instead.

The XSL-FO table model is quite close to HTML's table model. Table

19-1 shows the mapping between HTML 4.0 table elements and XSL

formatting objects:

Table 19-1

HTML Tables vs. XSL Formatting Object Tables

|

HTML Element |

XSL FO Element |

|

|

|

|

no equivalent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no equivalent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each

fo:table-and-caption contains an optional

fo:table-caption element and one fo:table

element. The caption can contain any block-level elements you care to

place in the caption. By default captions are placed before the

table, but this can be adjusted by setting the caption-side

property of the table-and-caption element to one of

these eight values:

before

after

start

end

top

bottom

left

right

For example, here's a table with a caption on the bottom:

<fo:table-and-caption caption-side="bottom">

<fo:table-caption>

<fo:block font-weight="bold"

font-family="Helvetica, Arial, sans"

font-size="12pt">

Table 19-1: HTML Tables vs. XSL Formatting Object Tables

</fo:block>

</fo:table-caption>

<fo:table>

<!-- table contents go here -->

</fo:table>

</fo:table-and-caption>

The fo:table element contains

fo:table-column elements, an optional

fo:table-header, an optional fo:table-footer,

and one or more fo:table-body elements. The

fo:table-body is divided into fo:table-row

elements. Each fo:table-row is divided into

fo:table-cell elements. The fo:table-header

and fo:table-footer can either be divided into

fo:table-cell or fo:table-row

elements. For example, here's a simple table that includes the first

three rows of Table 19-1 above.

<fo:table>

<fo:table-header>

<fo:table-cell>

<fo:block font-family="Helvetica, Arial, sans"

font-size="11pt" font-weight="bold">

HTML Element

</fo:block>

</fo:table-cell>

<fo:table-cell>

<fo:block font-family="Helvetica, Arial, sans"

font-size="11pt" font-weight="bold">

XSL FO Element

</fo:block>

</fo:table-cell>

</fo:table-header>

<fo:table-body>

<fo:table-row>

<fo:table-cell>

<fo:block font-family="Courier, monospace">

TABLE

</fo:block>

</fo:table-cell>

<fo:table-cell>